When your child is diagnosed with mild scoliosis it’s best to learn all you can. At Scoliosis 3DC®, education is central to our mission. Everything we do is designed to empower families coping with scoliosis whether it be mild, moderate or severe. This post is written to help you gain knowledge about mild scoliosis and provides information you may not hear from your doctor. Once you consider all the facts, we think you may agree with us that being proactive for mild scoliosis may be your best plan.

Mild scoliosis is a spinal curve with a Cobb angle of 10 to 25 degrees – as measured on x-ray. The definition varies by source, but this is a generally accepted range. When a child shows signs of scoliosis – detected in a school screening, by a pediatrician, a chiropractor, coach or loved-one – a common path may be a visit to an orthopedic surgeon. That visit may go something like this, “Your child has mild scoliosis. At the moment, it’s nothing to be concerned about. Let’s watch and wait. Check back in four or six months and we’ll re-xray.” (The time frame recommended will depend on a variety of factors which we will get into shortly.)

The recommendation to watch and wait for mild scoliosis is likely a result of SRS – Scoliosis Research Society – guidelines for scoliosis treatment and/or an individual doctor’s treatment philosophy. The SRS is an organization of spinal surgeons who treat scoliosis and other spinal deformities. In general, their treatment guidelines for scoliosis can be summarized as follows:

Mild scoliosis: watch and wait

Moderate scoliosis: brace

Severe scoliosis: surgery

The watch and wait stance is puzzling. When mild scoliosis is diagnosed and the ‘treatment strategy’ offered is observation only, many parents are uneasy (understandably so) because that is counterintuitive! Most parents prefer to attack a health problem head on whenever possible and utilize less invasive interventions before more invasive methods are needed later in on the case of a progressive scoliosis.

‘Observation’ may have its roots from a report issued by the Research Committee of the American Orthopedic Association, 1941 (1) which concluded that exercise has no effect on scoliosis. These conclusions were the result of surveys of doctors whose patients had tried general exercises of various types. Since that time, the consensus in the orthopedic community has been to disregard exercise for scoliosis, despite the fact that more targeted scoliosis specific exercises (i.e. the Schroth method) now exist in the US. We find it unfortunate that most MDs deny the efficacy of scoliosis exercise. Parents wanting to do everything possible to halt the possibility of curve progression need to have every available option at their disposal.

Doctors tend to treat according to the law of averages and some may view treatment for mild scoliosis as overtreatment. The truth is that not every case of mild scoliosis will progress, but many do. For parents, it’s hard to know who to trust or where to turn. From our point of view, there are flaws in the ‘wait and see’ stance that you should be aware of as a parent of a child with scoliosis. We know far too many parents who, to their dismay, followed the observation only advice just to watch their child’s scoliosis worsen with subsequent x-rays.

Just so you are aware, scoliosis progression is, by definition, a 5º or more increase in Cobb angle from one x-ray to the next. You should also consider that there is a 5º margin of error when it comes to Cobb angle measurement among practitioners. This further complicates suggestions based solely on Cobb angle.

With scoliosis, the Cobb angle must be considered in combination with other risk factors (we will get to these), as well as clinical presentation. If it’s a slight scoliosis and your child is skeletally mature, we aren’t necessarily advocating treatment. However, if your child has considerable growth potential, or is approaching the moderate phase of scoliosis, it may be best not to wait and see.

When a patient approaches or reaches the cusp of mild and moderate scoliosis, most practitioners will advocate bracing in a growing adolescent at ~25°. However, given one doctor’s stance that 68% of curves ≥20° will progress (2), why would you risk waiting to start any type of treatment deemed worthy if your child is close to the mark?

Mild scoliosis and risk of progression

When mild scoliosis is diagnosed, understanding the factors that can play a role in progression will help in your decision making process. In general, the more growth potential the child has when they are diagnosed, the greater the risk of progression. There are no hard and fast rules to determine who will progress and who won’t. Progression may be a slow and drawn-out, it may come rapidly, or not at all. When progression happens quickly it usually happens during a sudden growth spurt. A mild scoliosis this week can become moderate within a few weeks, or months. Individual risk factors may help to tell the story of the way scoliosis progression might play out for your child.

The following factors, alone or in combination, are used to gauge scoliosis progression risk:

- Juvenile scoliosis – a curve detected in a child under 10 years old is at high risk

- Girls who have not yet experienced menarche, or recently experienced menarche

- The presence of certain comorbidities

- A family history of scoliosis

- Risser sign (see below): the lower the Risser stage, the higher the risk of progression

- Cobb angle: the higher the degree at diagnosis, the greater the risk (i.e. 14º vs. 24º)

- Progression has already occurred

- Hyperflexibility, joint laxity, etc.

- Significant spinal rotation and/or postural imbalance

- Sex: Mild scoliosis is prevalent in boys and girls at equal rates. However, girls with scoliosis are 8 times more likely to progress. That said, boys are known to have prolonged growth into their late teens so they are at risk for longer and you should remain vigilant.

Mild scoliosis and Risser sign

As previously mentioned, scoliosis can progress during periods of rapid growth. Risser stage plays an important role in predicting progression risk. It’s an estimation of a child’s bone maturity based on how much ossification of the iliac apophysis has occurred. Risser is graded on a scale from 0 (skeletal immaturity) to 5 (skeletal maturity). As your child’s Risser increases, the amount of projected growth decreases. If your child is a Risser 0, 1, 2 they still have significant growth potential. At Risser 3 and 4 the rate of growth has slowed, and at Risser 5 your child is considered skeletally mature. With that said, a higher Risser grade means less chance of positively influencing the scoliosis (through scoliosis-specific exercise or corrective bracing), though we do have documented cases of patients showing scoliosis improvement at every Risser stage.

Progression Factor

In 1984, Lonstein and Carlson used a combination of three of the factors: Cobb angle, Risser sign and age, to create an equation – progression factor – to predict progression risk in patients with Cobb angles up to 29º (3). Their method has its limitations and has been criticized on the basis that any method of predicting progression that relies too heavily on Cobb angle is likely to be inaccurate.

Today, there is still no widely accepted method that scoliosis physicians agree upon to calculate progression risk in specific cases. To our way of thinking, the lack of conclusive methods to predict who will progress and who will not, or to what degree, only serves to support the case for proactive treatment for mild scoliosis when patients have one or more of the risk factors previously listed.

Functional vs. structural scoliosis

When a mild scoliosis is diagnosed you should determine if the scoliosis is functional (non-structural) or structural. Functional curves are flexible and can be mobilized. They have the potential to be corrected with specific postural re-education and scoliosis exercises prescribed according to curve pattern and clinical presentation. Functional curves are sometimes caused by other skeletal imbalances, for example, one short leg or as a result of an injury. However, functional curves can become structural over time.

In contrast, structural curves are fixed with some degree of limited flexibility (unique to each patient). These curves exhibit a fixed rotational prominence. As a patient becomes more skeletally mature, structural curves can become more fixed and more rigid. The likelihood of making a significant correction via scoliosis-scoliosis-specific exercise wanes, but even adults may be able to achieve postural improvement, to some degree.

For added insight into mild scoliosis you should understand how a curvature affects the spine during growth. Scoliosis is a three-dimensional condition. It affects the coronal plane (as viewed on AP/PA x-ray), the sagittal plane (the spine viewed from the side) and the transverse plane (the spine as viewed from above, or the rotational aspect). When the spine and trunk are malaligned in three dimensions, the asymmetric body is vulnerable.

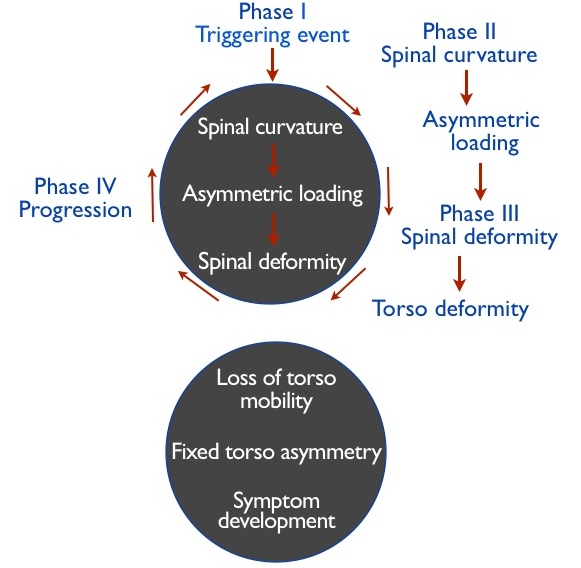

Asymmetric loading of the spinal joints can trigger a process known as “the vicious cycle of scoliosis.” Asymmetric loading results in added pressure on the spinal joints on the concave side of the curve(s) with less pressure on the convex side. Growth that occurs during this process results in less growth on the concave side and more on the convex side. When the body is in this state it can lead to further instability, fixed torso and curve progression. Unless the vicious cycle is interrupted, the patient is at continued risk. Martha Hawes discusses this in her paper entitled, The transformation of spinal curvature into spinal deformity: the pathological processes and implication for treatment, where she states, “Spinal curvatures can routinely be diagnosed in early ages BEFORE pathological deformity can be induced due to spinal loading” (4).

Mild scoliosis, what’s a parent to do?

Now that you are aware of the specific risk factors for your child and the concept of the vicious cycle, you may have a better understanding of why we advocate being proactive rather than waiting to treat scoliosis for many children. Another little known fact to be aware of is that research states that scoliosis curves held to under 30 degrees are far less likely to progress in adulthood (5). It’s another reason why it’s better to get ahead of the curve, before progression happens, whenever possible. This is especially important for early onset scoliosis, for girls who have not yet experienced menarche and for children or adolescents who are mild but extremely decompensated.

Until doctors can predict, with certainty, who will progress and when, or who won’t, simple conservative interventions are the path to an improved prognosis. Our facility has used protocols that include postural re-training and curve pattern-specific scoliosis exercises for nearly two decades. Depending on a child’s estimated progression risk, the option for corrective bracing may also be considered for patients.

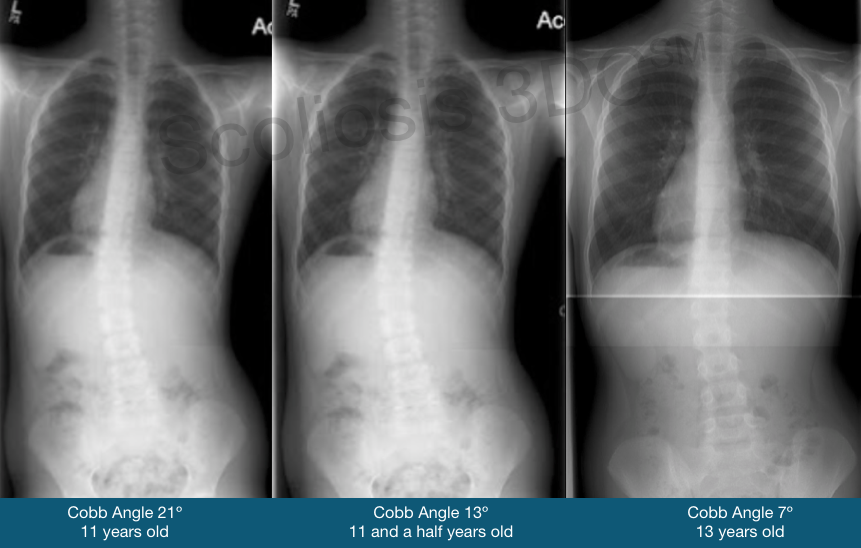

To see other cases of children and adolescents who’ve improved their scoliosis in the early phase, please link to our mild scoliosis treatment results section. Whether your child has a slight scoliosis or one on a more upward trajectory, curve-pattern-specific instruction and/or bracing may make a significant impact.

A few final thoughts…

Only you can weigh the amount of risk you are willing to tolerate when it comes to potential scoliosis progression. Hopefully, this post has provided added insights.

Scoliosis-specific exercise treatment is a relatively new concept in the US. We’ve made some inroads into awareness, but reversing years of dogma takes time. If your child has scoliosis now, you don’t have the time to wait for the shifting of establishment attitudes. Delaying treatment, or choosing the wrong treatment approach or practitioner, may not be in your child’s best interest. We’ve said it before and it’s worth repeating, once scoliosis progresses it’s much harder to make a positive impact on the curve(s) with conservative treatment approaches.

When it comes to scoliosis during growth, you need to stay on top of the situation. Make a game plan. When pursuing a proactive treatment approach, include your child in the decision-making process. He/she is the one who must take ownership of the process. Our patients with mild scoliosis are almost always successful. It’s because we help them understand their unique curve pattern and what’s at stake. Once patients understand what needs to be done, most kids step up to the plate and take responsibility. When kids learn what to do during the mild phase and can keep scoliosis mild (or even improve it a bit), scoliosis exercise is a temporary situation – not a lifetime commitment. One research statistic implies that ‘curves held to under 30º rarely get worse after skeletal maturity’. Our outpatient training for mild scoliosis is fairly simple. Specific recommendations are made on a case-by-case basis.

We introduced the Schroth Method in the US in 2007 and have since included updates which make the method simpler for our patients. We can confidently say that no one offers a program quite like ours, or with a more passionate, caring and experienced team. We are committed to educating and empowering patients with scoliosis at every phase. We think you deserve a choice when it comes to scoliosis treatment. To learn more, give us a call. We are here to help.

Last updated: February 3, 2025

References:

1 – Hawes, M. C. Scoliosis and the Human Spine. West Press, Tucson, Arizona. (2002)

2 – Placzek, J. D., & Boyce, D. A. (2017). Scoliosis. In Orthopaedic physical therapy secrets(3rd ed., pp. 470-473). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Health Sciences.

3 – Lonstein JE, Carlson JM. The prediction of curve progression in untreated idiopathic scoliosis during growth. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:1061–1071.

4 – Hawes M. Impact of spine surgery on signs and symptoms of spinal deformity. Pediatr Rehabil 2006, 9(4):318-39.

5 – Weinstein S. et al. Health and Function of Patients With Untreated Idiopathic Scoliosis – A 50-Year Natural History Study. JAMA, 2003;289(5):559-567.