Yoga for scoliosis is a popular trend but many poses can cause long-term problems when performed properly, or improperly. Christa Lehnert-Schroth, PT shared Dr. Marc’s concerns and the two had discussed the harms of yoga for scoliosis at length on more than one occasion. Our stance on yoga is unpopular with some and in direct opposition to what some ill-informed marketers, surgeons, yogis, and authors recommend. All too often, however, we have encountered patients who have done yoga for scoliosis for years thinking they are benefitting their spine, but have only exacerbated their curve(s) or experienced increased pain.

While yoga is being used increasingly as a ‘treatment’ for scoliosis, it is often without a full understanding of its effect on the scoliotic frame. Having scoliosis, and exercising with scoliosis, poses unique problems because of one’s inherently complex and asymmetrical configuration. While seemingly beneficial for the symmetric body, yoga was not created specifically for the scoliotic spine.

A recent WSJ article suggested that the yoga side plank may be helpful when performed appropriately. The problem with that is that some patients and practitioners may conclude, inappropriately, that yoga for scoliosis, in general, can be used as a treatment. This is a misnomer because there are, in fact, many poses that may be harmful. Patients need to understand the big picture about yoga for scoliosis.

Exercising with scoliosis should take into account each person’s spinal configuration to avoid inducing harm. Patients must use caution with several types of yoga poses and the patient must learn how each yoga exercise impacts their unique spine. This is why education about individual curve pattern is the first component of our scoliosis back school.

Yoga, in particular, should not be used therapeutically for a patient’s pathologically asymmetrical torso without comprehensive physiological and anatomical knowledge and training in the biomechanics of scoliosis. Fundamentally, certain yoga poses are harmful because they only consider the primary curve while ignoring the secondary curves, not taking into account the exercise’s full effect on the spine and torso. Yoga poses that can create problems include a variety of back-bending, torso-rotation, combination, and shoulder stand poses.

According to Schroth principles, the trunk is divided into three body blocks. Each block of the trunk is rotated pathologically against the adjacent block above and/or below. For example, in patients with ‘three-curve-scoliosis,’ the shoulder girdle and the pelvic girdle typically rotate in the same direction while the rib cage block (center block) is rotated in the opposite direction. Specific curve-pattern classification (there are several pattern variants and among those there are nuances) is essential before instruction.

The point is that scoliosis is not simply a laterally shifted spine as shown on a two-dimensional X-ray, but rather the entire upper body is affected. The rotated ribs force the attached vertebrae to be misshaped and misaligned.

According to Schroth method principles, poses that bend and twist or rotate the torso, or a combination thereof, or those that place the body weight on the shoulders, whether repetitively or in a prolonged static position are potentially harmful to the scoliotic spine.

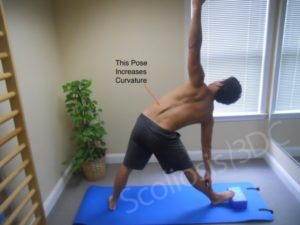

Since there are so many yoga poses, we could fill a volume writing about the potential risks of each yoga pose and its implications for individual curve patterns. For simplicity sake, let’s consider a lateral bending exercise, the triangle pose, to make the point because it is one of many harmful poses recommended in a popular yoga for scoliosis program.

The patient in the photo has a right thoracic curve. He is laterally flexing to the right. When considered alone, this can have a positive effect on the right thoracic curvature. The goal in this case, when going to the right, is to open the left thoracic concavity (widen the left rib cage) allowing increased respiration into the collapsed side. This much is appropriate.

However, simultaneously, a strongly contraindicated effect occurs in the adjacent lumbar region. When the patient bends to the right, it further compresses the lumbar concavity. This pose lengthens the left lumbar muscles on the convex side and further shortens the lumbar muscles on the concave side thereby increasing the lumbar curvature. The right free floating ribs (#11 and 12) are shifted to the left, downward and medially, creating an increased lumbar prominence which exacerbates the left lumbar hump. This pose also increases spinal joint loading and vertebral wedging which can have a negative effect on the intervertebral disc.

Now consider this photo in which the same exercise is performed to the left side (it is common for yoga exercises to be performed bilaterally). The patient assumes a wide stance and bends the torso to the left. The left hand reaches toward the left foot and the right arm stretches over the head. This motion exacerbates the right thoracic curve as is clearly visible. This movement compresses the left rib cage and left thoracic concavity and there is also an increase in the right dorsal rib prominence.

The counter-pose cannot be performed in the hope of achieving balance because, for the scoliotic patient, both versions are mechanically incorrect in the context of the entire spinal and torso structure.

At Scoliosis 3DC® we are not anti-yoga, in fact, our Schroth therapist Kim is a certified yoga instructor. However, we want to make sure scoliotics understand how to avoid inducing progression and pain. Some yoga poses are harmless; maybe a few are even helpful, but patients must understand that yoga is not suitable as a treatment for scoliosis because the poses are not curve-pattern specific and were not designed for the complex asymmetrical spinal structure and musculature.